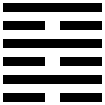

Introduction To The I Ching

I was first introduced the the I Ching in 1989. The friend who shared it with me said something that still echoes in my head to this day; “No matter what you believe in, there is good wisdom on every page of this book.” At that time I maintained a compulsive skepticism, so it was a welcomed approach. Within a few short years, the book had surfaced in numerous places. Whether on the shelf of a store or library, or in the homes of new, interesting friends, it captured my attention. I proceeded to study and utilize the work with steady devotion. While the complexity, depth and history of the I Ching benefits greatly from continued study and practice, I discovered that it can also be immediately accessible for one who has a sincere interest.

At first glance, the book can be truly daunting, filled with language and references that are obscure, cultural, historical, and seemingly outdated. However, I encourage anyone curious to dive in anyway. Filled with symbols and metaphors, the I Ching shares something with mythology. The messages and meanings of such things have the capacity to influence our consciousness without requiring a comprehensive academic or intellectual understanding of them. With attention, we may work with and interpret these symbols and it certainly can lead to a greater understanding and benefit, but it is not necessary in order to get involved.

Working with symbol and metaphor may take practice for many people. Faced with the subtlety of it, it may be tempting to seek out a more “modern” translation, that gets straight to a topic you are familiar with or references our contemporary world and it’s challenges. I certainly would not discourage anyone from pursuing such translations, and some of those available provide quality insights. I would offer some context and perhaps a caution, however. Some modern translations of traditional books of wisdom, in an effort to simplify and make it accessible can overlook, discard, or narrowly interpret the source material. My study of the I Ching has been predominantly through the Richard Wilhelm translation. More on that can be found here. For more on symbols, their use and misuse, I go into the topic more deeply here

The I Ching, or “Book of Changes” is precisely that. It addresses the nature of change, which has been described as a universal constant. It is a body of wisdom devoted to understanding “the nature of the time” and how to adapt to the myriad of changes that occur. There is perhaps nothing more common than the impulse to make a seemingly chaotic and dangerous existence hold still and adhere to safer and more predictable form. Our sense of safety and survival often compels us to pursue such a course. Despite the apparent benefits of this approach, we all too often discover that when we resist change, we stop growing, stop learning, and our lives become inert and, arguably, no easier. The wisdom of the I Ching recognizes that the nature of our existence is undergoing continuous changes, and rather than trying to fix things in place, advises us in how to blend with the circumstances we encounter.

The I Ching is by no means the only method that instructs about staying present, adaptation, or “going with the flow”. We see these practices overlapping in many traditions, particularly (but not exclusively) those rooted in eastern culture. If you are familiar at all with Zen, Buddhism, Taoism, Tai Chi, or Aikido (just to name a few), you will find that the I Ching blends nicely with these “ways”. In particular it can lend a great deal of substance for study and practice over time.

If we were to compare change to water, many of these traditions are about learning to swim. The I Ching joins them with detailed guidance for the many different kinds of water we might encounter. There are droughts, ponds, swimming pools, rivers, calm seas, and big oceans. If you aren’t sure where to start, just dip a foot in.